EDF Staff | April 15, 2013

By: Jake Hiller and Chris Riso

The United States spends more than $108 billion on energy for commercial buildings each year[i], and that is too much. It is possible to do more while spending less on energy. However, optimizing a building’s energy performance takes time and money – two things not typically in surplus for facility managers.

The fact is organizations face many barriers to implementing energy-saving projects, which have nothing to do with technology and everything to do with the way people make decisions.

Environmental Defense Fund created its EDF Climate Corps program to solve this problem. EDF has worked deep within hundreds of leading organizations across the nation to uncover energy savings for commercial buildings, finding an average of $1 million for each organization involved.

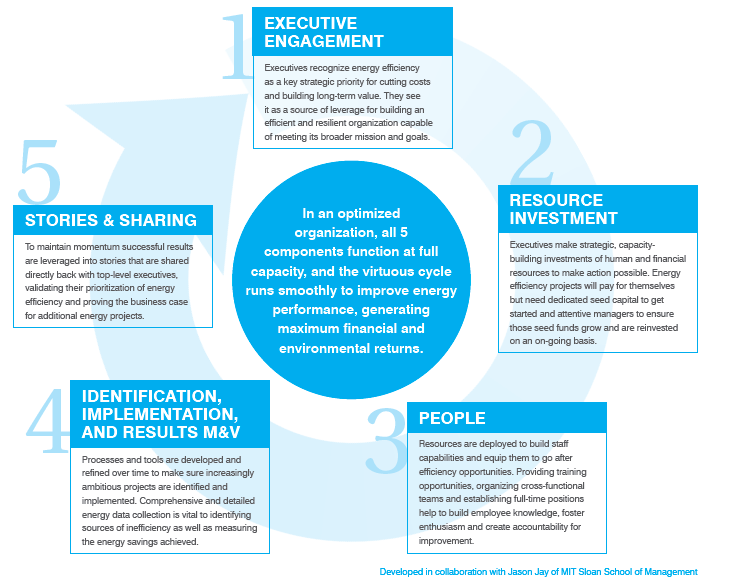

EDF has learned that saving money by saving energy is more of an art than a science. It is about understanding how decisions are made in organizations and how resources are allocated. Recently, EDF and MIT published a roadmap for facility managers looking to optimize energy performance called The Virtuous Cycle of Organizational Energy Efficiency. It is a model of change proven to apply across even radically different organizations with the five powerful, interdependent components listed below.

The Virtuous Cycle of Organizational Energy Efficiency

The components of the “Virtuous Cycle” model affect one another for better or worse. When the performance of one component improves, the performance of other components is made more likely to improve in a “virtuous cycle” of positive feedback. Conversely, if the performance of one component worsens, this can negatively impact the performance of other components through a “vicious cycle” of negative feedback. In an optimized organization, all components function at full capacity, and the virtuous cycle runs smoothly to improve energy performance, generating maximum financial and environmental returns.

1. Executive Engagement

Top-level executives recognize energy efficiency as a key strategic priority for generating cost savings and building long-term value. They shift from seeing energy as an inevitable and growing cost, and instead see its optimization as a source of continuous leverage for building an efficient and resilient organization capable of meeting its broader mission and goals.

2. Resource Investment

In order to empower their organization to capture energy savings, executives make strategic, capacity-building investments to free up the necessary human and financial resources to make concrete action possible. Energy efficiency projects will pay for themselves but need dedicated seed capital to get started and attentive managers to ensure those seed funds grow and are reinvested on an on-going basis.

3. People

Resources are deployed to build staff capabilities and equip them to go after efficiency opportunities. Providing training opportunities, organizing cross-functional teams and establishing full-time positions all help to build employee knowledge, foster enthusiasm and create accountability for improvement. A workforce that feels ownership and responsibility for its energy use at all levels and is actively encouraged by leadership to work toward a shared vision of efficiency will maintain the momentum needed to make real progress.

4. Opportunity Identification, Implementation, and Measurement &Verification

In order to aid the organization's staff, effective processes and tools are developed and refined over time to make sure increasingly ambitious projects are identified and implemented. Comprehensive and detailed energy data collection is vital to identifying sources of inefficiency and measuring the energy savings achieved through specific interventions--generating the verified financial and environment results that prove the benefits of taking action in the first place.

5. Stories and Sharing

To maintain momentum beyond a first round of projects, successful results are leveraged into stories that are shared directly back with top-level executives, validating their prioritization of energy efficiency as a key strategy and proving the business case for doing additional energy projects. By re-engaging the executives continuously, success stories keep energy performance at the top of the agenda and encourage the investment of additional human and financial resources to go after even bigger wins, keeping the virtuous cycle spinning for yet another round.

Success Story: Shorenstein optimizes the Virtuous Cycle

Building momentum in the Virtuous Cycle of Organizational Energy Efficiency requires persistent, well-targeted effort. The following is an example of one company that is making progress toward comprehensive, self-reinforcing energy management practices.

Shorenstein Properties is a real estate company that owns more than 23 million square feet of commercial building space across the United States. The company has participated in EDF Climate Corps since 2009.

In 2010, Shorenstein’s engineering managers completed an “Energy Savings Tour,” a survey of energy projects across their portfolio of commercial buildings. As a part of the Energy Savings Tour, the engineering managers spent three months visiting all properties in the portfolio. They walked through each building with the chief engineer and property manager to inventory and prioritize efficiency projects. From this tour, they identified more than 300 energy-saving strategies—some big, some small—in almost every building system category. These included everything from Building Management System tuning opportunities to lighting retrofits to installing Variable Frequency Devices on fans and pumps. At this time, the energy managers also set a goal to achieve 3.5 percent energy savings portfolio-wide.

Once all of the project opportunities had been identified, the projects were then prioritized by no-cost, low-cost or capital cost. The no- and low-cost items were typically easy operational changes, or “low hanging fruit,” and were implemented right away. The capital cost items were recommended for budget approval.

In 2011, Shorenstein wanted independent evaluation and verification of their actual savings and environmental impact from the projects implemented as a part of the Energy Savings Tour. But there was a problem. This type of performance evaluation for corporate energy efficiency programs was relatively uncharted territory.

For that reason, Shorenstein engaged EDF Climate Corps to adapt the methodology used for verification of utility-scale energy efficiency programs and confirm evaluation techniques.

Overall, this evaluation showed that the projects implemented from the Energy Savings Tour reduced energy consumption by 5.1 percent across the entire commercial building portfolio, far exceeding their 3.5 percent energy savings goal. The evaluation also confirmed $1.7 million and 12.3 million kilowatt hours saved annually as well as 4,800 metric tons of annual greenhouse gas emissions avoided. The resulting savings was equivalent to taking more than 1,000 homes off the electric grid. The payback period for the program was just six months.

Measuring the impact of the Energy Savings Tour reinforced the Virtuous Cycle propelling it forward for another round at Shorenstein. Below are some specific examples of how the Shorenstein case study above proves the Virtuous Cycle framework.

1. Executive Engagement

When a clearly defined goal is put into place, management will pay close attention to the efforts involved. In Shorenstein’s case, the Energy Savings Tour produced energy and financial savings that easily surpassed the goals set by energy managers. This resonated with Shorenstein’s senior management and validated the notion that environmental and financial outcomes do align.

2. Resource Investment

The motivations of executives need to translate into resource provisions that support employees and reward them for identifying and implementing projects. In the Shorenstein case, energy managers were able to spend four months identifying energy efficiency opportunities at 33 of the company’s properties. This investment in time and valuable resources enabled Shorenstein to identify not only low-hanging fruit, but a large portfolio of projects that can enable energy savings over the long term.

3. People

Hiring a dedicated corporate energy or sustainability manager ensures attention is maintained and focus is kept on energy saving opportunities. The Energy Savings Tour and experience with EDF Climate Corps led to Shorenstein’s decision to create the new role within the organization of Sustainability Program Manager to increase productivity.

4. Identification, Implementation, and Measurement & Verification

The Energy Savings Tour resulted in impressive savings, but it uncovered even greater opportunities for the future. The company is pursuing several strategies to enable deeper cuts to energy consumption. Specifically, Shorenstein is addressing the human aspects of energy use in buildings. In commercial offices, tenant behavior determines up to 70 percent of a building’s energy use, so Shorenstein has launched its “Flip the Switch” tenant engagement program to catalyze tenant action on energy efficiency and environmental performance. The program combines an educational presentation series with a customized sustainability resources website for tenants.

5. Results and Stories

In order to demonstrate progress towards their energy savings goal, Shorenstein made the effort to engage EDF Climate Corps to quantify the success of its Energy Savings Tour. In adapting an evaluation method for Shorenstein’s specific needs, the EDF Climate Corps fellow optimized the Virtuous Cycle of Organizational Energy Efficiency and broke down internal barriers. In the future, this evaluation method will enable Shorenstein to know the effectiveness of its efforts and accurately communicate success. Furthermore, sharing its story will help Shorenstein to engage stakeholders within and external to the company, and once again affirm support from executive management.

Shorenstein’s corporate energy efficiency program provides an innovative example of how companies are cashing in on sustainability strategies with positive economic and environmental impact. With its Energy Savings Tour, efficient allocation of resources and a fresh new approach to measuring and verifying success, Shorenstein has established momentum in implementing its energy efficiency program. It takes investment in both time and resources, but optimizing the Virtuous Cycle of Organizational Energy Efficiency can provide significant benefits for any company.

| Virtuous Cycle Stage | |||||

| Executive engagement | Resource investment | People and tools | Actions and Wins | Results and stories | |

| Cause of friction | Diminishing attention | Diminishing budget | Diminishing capability | Diminishing opportunity | Diminishing bandwith |

| How Shorenstein addressed the problem | Public goals and verified success ensures top level buy-in | Dedicated resources and time allocated to energy efficiency enables action | Established evaluation and verification methods enable companies to identify success | Inventorying the full set of potential projects identifies projects for now and the future | Identifying and sharing results makes success visible to stakeholders |

| Additional practices found in the EDF Climate Corps network | Hiring a dedicated corporate energy manager ensures attention is maintained | A dedicated energy efficiency fund and/or revolving loan fund ensure capital is always available | Building energy performance into personnel evaluation and rewarding success motivates employees | A real-time and up-to-date database of projects enables decision-makers to see available opportunities | An energy scorecard identifies top performing projects while also revealing learning opportunities |

This article was originally posted in the April 2013 issue of Building Operating Management at facilitiesnet.com/BOM.